Olives picked for home curing (photo by Diana Lundin) |

Traditional foodways range from herb and vegetable gardens to curing olives, making wine, to various forms of socialization around food (family dinners to festive occasions). It is no coincidence that many Italian families are involved in some aspect of food production and distribution, often as family-owned businesses. In the past these included: canneries, pasta and cheese production, grocery stores, delis, and restaurantsó many of which continue today (e.g., Costa Pasta Mfg., Claroís Markets). In California furthermore, Italians have historically played a central role in wine and agriculture, as well as in (San Pedro) fisheries (Further reading: Gloria Ricci Lothrop, Italians of Los Angeles, Historical Society of Southern California, 2003.)

Street food vendor at the San Gennaro festival 2004: fresh raw seafood by Frankie |

Snails (lumache) picked in the wild and prepared alla romana (Roman style: with tomato, wine, garlic, and wild herbs) |

Traditional, homemade Christmas sweets stuffed with figs, nuts and candied fruit |

Evolutions. Foodways are in constant flux as Italian Americans are expanding their culinary vocabulary, in part due to the general Italianization of California cuisine, the high status of Italian cuisine, and the increasing availability and decreasing cost of Italian products in Southern California, , many more produced locally than once was the case. Mozzarella di bufala no longer costs $14/lb. or radicchio rosso $7.98/lb., as they did when they first came on the market decades ago! These and countless other Italian food items have gained wide currency across Southern California, as they have elsewhere. While they are not as common as pizza and pasta, signs point in that direction.

Frying sweets at the Festa di San Pietro picnic, San Pedro |

Preparing pasta at the Festa di San Pietro picnic, San Pedro (Stefano Finazzo on the right) |

Further reading on food and wine in Italian American life by Luisa Del Giudice:

-"Ischian Cultural Sites on the San Pedro, California Map" ('Siti culturali ischitani sulla mappa di San Pedro, California') in Pe' terre assaje luntane: L'emigrazione ischitana verso le Americhe, Ischia, 2007

- ì`Wine Makes Good Bloodí: Wine Culture Among Toronto Italians,î in Ethnologies, 2001, Vol. 23, number 1, 1-27.

- ìPastaî (46-52) and ìSlow Foodî(288-89), in Encyclopedia of Food, Vol. 3, ed. by Solomon H. Katz, New York: Charles Scribnerís Sons, Thomson Gale, 2003.

- ìItalian American Food and Foodwaysî (245-248), in S. LaGumina, F. Cavaioli, S. Primeggia, J. Varacalli, eds., The Italian American Experience: An Encyclopedia, New York: Garland, 2000.

- "The `Archvillaí: An Italian Canadian Architectural Archetype," in Luisa Del Giudice, ed., Studies in Italian American Folklore, Logan: Utah University Press, 1993:53-105. Chosen official publication of the American Folklore Society.

- ìFeeding The Poor: St. Joseph's Tables in Los Angeles,î in Lucia Re and Claudio Fogu, eds., Italy in the Mediterranean (special issue of: California Italian Studies, 2009.)

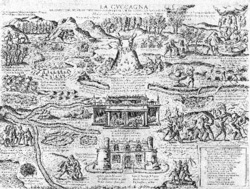

Cuccagna: Mountains of Cheese, Rivers of Wine. The mythic Land of Cockaigne (Lubberland, Schlaraffenland, Panigons, Oleana, or the Big Rock Candy Mountain), popular since the Middle Ages all across Europe, projected a gastronomic utopia, ìpoor manís paradise,î or ìcollective dream of the hungry massesî (Camporesi 1978). In its Italian variant, it featured mountains of cheese, rivers of wine and other sensual delights, as well as punishment for those who worked. This Topsy Turvy world represented a time and place of perpetual feasting. This mythic land survived in Italian popular consciousness for centuries, became one of the driving myths behind mass migration to America (otherwise known as Cuccagna) and although transformed, still animates aspects of Italian and immigrant culture in America. The greased pole found at public festivals is known as líalbero di Cuccagna. Climbing to the top, one finds special foods, perhaps money, and other prizes. Further reading: Luisa Del Giudice, "Paesi di Cuccagna and other Gastronomic Utopias," in Imagined States: National Identity, Utopia, and Longing in Oral Cultures, ed. by Luisa Del Giudice and Gerald Porter, Logan: Utah State University Press, 2001: 11-63.

Cuccagna: Mountains of Cheese, Rivers of Wine. The mythic Land of Cockaigne (Lubberland, Schlaraffenland, Panigons, Oleana, or the Big Rock Candy Mountain), popular since the Middle Ages all across Europe, projected a gastronomic utopia, ìpoor manís paradise,î or ìcollective dream of the hungry massesî (Camporesi 1978). In its Italian variant, it featured mountains of cheese, rivers of wine and other sensual delights, as well as punishment for those who worked. This Topsy Turvy world represented a time and place of perpetual feasting. This mythic land survived in Italian popular consciousness for centuries, became one of the driving myths behind mass migration to America (otherwise known as Cuccagna) and although transformed, still animates aspects of Italian and immigrant culture in America. The greased pole found at public festivals is known as líalbero di Cuccagna. Climbing to the top, one finds special foods, perhaps money, and other prizes. Further reading: Luisa Del Giudice, "Paesi di Cuccagna and other Gastronomic Utopias," in Imagined States: National Identity, Utopia, and Longing in Oral Cultures, ed. by Luisa Del Giudice and Gerald Porter, Logan: Utah State University Press, 2001: 11-63.

A 17th-century Italian print depicting the mythic land of Cockaigne (Paese di Cuccagna) |

Gardens The Italian presence in California agriculture is well-known (e.g., Oberti olives, Del Monte fruits and vegetables, Mondavi vineyards, etc.), but even urbanized Italians have enjoyed their vegetable and herb gardens, and gardening formed, at least until recently, a traditional topic of discussion (something like discussing the weather) among Italians originally rooted in the land (as the majority of Italians in America were prior to emigrating from Italy). thatEarlier immigrations considered land used for non-food producing plants (i.e., flowers) largely as wasted space better used for fruit trees, vegetables, and herbs. But while gardens may still be an important part of Italian home life (it is difficult to gauge to what extent), their importance is becoming secondary as California's abundant and varied agriculture increasingly produces foods once cultivated only in private gardens (e.g., basil, Italian parsley, rosemary, arugula or rucola, radicchio, etc.). If the majority of Italian Americans no longer grow vegetables such as eggplant, tomatoes, peppers, artichokes, fava beans, and so forth, many continue to grow herbs, despite the fact that they are now widely available on grocersí shelves and at farmersí markets. Vegetables, fruits, and greens difficult to find in markets may still be grown: cicoria, figs, olives, etc. Although vegetable preserving is not all too common today, it still survives, as does olive curing in several central and southern families in whose home regions olives grew, that is Central and Southern Italy. Slowfood sustainable agriculturalists, locovores, and the new food consciousness, are all helping to revive traditions of home-style food processing (See: "tomatomania" events, as well as olive curing seminars, FOOD ASSOCIATIONS, Slowfood).